A Collaboration, of some called psychotherapy; bonds filled of expressions, and expressions filled of meaning

Tom Andersen, ISM, Breivika, 9037 Tromsø, Norway

„…And we must not advance any kind of theory. There must not be anything hypothetical in our considerations. We must do away with explanations, and description alone must take its place. And this description gets its light, that is to say its purpose, from the philosophical problems. These are, of course, not empirical problems; they are solved, rather, by looking into the workings of our language, and that in such a way as to make us recognize those workings: in despite of an urge to misunderstand them. The problems are solved, not by giving new information, but by arranging what we have always known. Philosophy is a battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language.“ (Ludwig Wittgenstein; Philosophical Investigations, # 109)

„A picture held us captive. And we could not get outside it, for it lay in our language and language seemed to repeat it to us inexorably.“ (Ludwig Wittgenstein; Philosophical Investigations, # 115)

Some background thoughts

We relate to our client by our descriptions of them. We do not relate directly to them, neither do we make correct nor representative descriptions of them. The same is the case for how the clients and the patients and the families relate to their reality; they also relate to it by their descriptions of it. Descriptions comprise much; f. i. stories, diagnoses and categories, conclusions, treatment plans, theses, memos, arguments, comments, meanings etc.

Some, not at least in the academy, have had the ambition to make accurate decriptions, ‚identical‘ descriptions. However, many have come to understand that every description of an other; either a client or a patient or a family, can only be one of many possible descriptions.

Descriptions are ‚build‘ in some few steps. First we notice something of the other, we sort out something = we make a distinction, that means that we pay attention to some of all what the person expresses. In the moment we give attention to something, we turn our attention away from all the other what the person says and does. If what the other says or does is a response to the therapist’s or researcher’s presented distinctions, either that is a question or a questionnaire, that question or that questionnaire will in itself only be one of many possible questions or questionnaires.

What we see and hear will be turned into a ‚picture‘. I put ‚picture‘ in signs to indicate that the picture comprises elements from all our senses; a ‚picture‘ has smells and tastes and movements and sounds. The ‚picture‘ gain meaning when it is put up against a background. Usually this background, which contain all what we have experienced before, emerges immediately and uncensored. When the ‚picture‘ is compared to the background it will be understood from what it likens in that background. Different people, f.i. different therapists and different researchers bring with them different backgrounds.

At home was the omniscient Encyklopedia, one yard in

the book shelf, I learned to read it.

But every person get their own encycklopedia written,

it grows in every soul

it is written from the birth and forward, the hundredthousand-

s pages are pressed against each other

and still there is air between them! As between shivering birchleaves

in the woods. The book of contradictions.

What is in it changes every moment, the pictures do retou-

che themselves, the words flicker.

A wave rolls through the text, followed by

the next wave, and the next …

(from ‚Short pause in the organ concert‘ by Tomas Tranströmer (1997)

Some times, maybe even not so seldom, do therapists and researchers try to make one common, dominant background, a concensus-background. This is thought to bring a certain and objective, evidence-based knowledge as the therapists and researchers try to exclude all of their personal elements in the background they understand from. The author of this chapter

does not only think that this is impossible and therefore a misunderstanding, but an unfortunate misunderstanding. This misunderstanding will easily create tensions and gaps between therapists and between academinians and between therapists and academinians, when they meet to share their understandings.

If an understanding or a meaning is to be shared with others it must be formulated in a written or talked text. Such formulations can be made differently, f.i. by help of a mathematical language that does not evoke emotions or by help of a metaphorical language that stirs much emotions. Formulations in themselves reduces the complexity of the reality it describes.

Both researchers and therapist must, as all other human beings, reduce all the impressions that come to them. If not it would be chaotic. Therefore they must reduce it all by concentrating on some relatively few elements, make distinctions, and leave the rest in peace. However, for the therapists and researchers it is important that they remind themselves that they, by help of their questions and methods and formulations, contribute to reduce and simplify the reality. In one or the other way.

Basic assumptions about inner ‚core‘ and outer bonds

„The aspects of things that are most important for us are hidden because of their simplicity and familiarity. (One is unable to notice something-because it is always before one’s eyes.)“ (Ludwig Wittgenstein; Philosophical Investigations, # 129)

When we start a therapeutic meeting we have actually already started it long ago. We do namely bring with us some basic ideas what a therapeutic meeting is and we have some basic ideas how we shall understand the human problems that are worked on in the therapeutic meetings.

I shall point to two different basic assumptions. The first, which is the most common and which is often met in the psychodynamic therapy world, can be said to belong to an individualistic perspective. The other which this chapter is based on, and is often met in the family therapy world, belongs to a communal perspective.

Within the first assumption one thinks that what a persons says or does is ‚driven forth‘ from an ‚inner core‘. Even though nobody has seen or touched this ‚inner core‘ there are many meanings of what it consists of. Formulations of what it can be are f.i. ego structures, defence mechanisms, conflicts, subconciousness, motivation, character, personality traits, etc. The therapist or researcher that bases his work on such assumptions will observe the outer signs, that means what the persons says and does, and based on these observations interpret what the ‚character‘ of the ‚inner core‘ is. Therapists and researchers will easily become an expert and can easily create monological talks where the expert asks and the observed one answers. The conversation will easily be composed of many small talks; one question is followed by an answer to it. Such monological talk will thoroughly be conducted in the perspective of the expert. The other person is there only to answer (Seikkula, 1995). The expert has often become used to think that she or he knows what is needed to reduce the human problem that is worked on, and also knows how to do it.

According to the other assumption a human being is connected to others by help of many bonds. These bonds comprise all different kinds of expressions, f.i. touches or looks or talks. The individuals particpate in these by help of their expressions. What one is saying is carried by a social voice. This voice reaches out to be received, and it is crucial that it is received, responded to and returned. We think that we have many social voices to be used in relation to different persons in different contexts. These social voices that evolve early in life, is initmately connected to all the inner voices we have that participate in our inner, personal talks. These inner voices, that are developed from the outer, social voices are ‚born‘ later in life than the social ones, are constantly active in the inner talks. Inner talks are for me the same as to think.

Ten assumptions about language and meanings

What I write here is very condensed compared to the sources it refers to. The written sources have been Ludwig Wittgenstein (Wittgenstein 1953,1980, von Wright 1990, 1994, Grayling 1988, Gergen 1994, Shotter 1996), Lev Vygotsky (Vygotsky 1988, Morson 1986, Shotter 1993,1996), Jacques Derrida (Sampson 1989), Michael Bakhtin (Bakhtin 1993, Morson 1986, Shotter 1993,1996) and Harold Goolishian (Anderson, 1995).

The collaboration with physiotherapists over the years, especially meeting Aadel Bülow-Hansen and Gudrun Øvreberg has had major influence on the development of these ideas (Øvreberg, 1986, Ianssen 1997). The sources have also been my own experiences to put these assumption into pratice. Not at least participating in a number of reflecting processes in very different circumstances have been significant to be able to formulate these ideas. These processes are open conversations where questions and answers come from all the perspectives that are present (Andersen 1995).

- Language is here defined as all expressions, which are regarded to be of great significance in the mentioned communal perspective. They are of many kinds, f.i. to talk, write, paint, dance, sing, point, cry, laugh, scream, hit etc, are all bodily activities. When this expressions, which are bodily, take place in the presence of others, language becomes a social activity. Our expressions are social offerings for participating in the bonds with others.

- We need the expressions to create meanings. If one of the kinds of expressions, f.i. the words or talking is not available, an other kind of expression, f.i. painting could make the creation of meaning possible.

- The expressions come first, then follow the meanings. Meanings are created. Harry Goolishian used to say: „We don’t know what we think before we have said it“.

- The meaning is in the expression, not under or behind. The meanings in the expressions, as f. i. in the words, are very personal, and some of the words will, when we hear them, bring us back to and re-experience something we have experienced before.

- The expressions are informative, which means that they tell something about us to others and also to ourselves. At the moment I think that I, when I speak out loud, first of all speak to myself. Since the words I express are so strongly connected to my understanding, I may, by listen carefully to what I say, investigate my own understanding. The expressions are also formative; we become those we become when we express ourselves as we do it. It would be more appropriate to say; „grandfather did always something kindly, so he became kind all the time“, instead of saying „grandfather was kind“ or „grandfather had so much kindness“. By using the verbes to be and to have without including time and context one can easily be bewitched by one’s own talking to believe that the described is static: ‚grandfather is kind‘; he has that character, or; ‚grandfather has much kindness‘; he has a kind personality. When we talk such to ourselves we can easily be supplied with the ideas that a human being both have character and personlity.

- The expressions, both in the inner and personal talks and those in the outer and social talks are accompanied by movements. Those who follow the inner talks are smaller and nuanced, as those that follow the outer talks are bigger, f.i. waving hands Sometimes both therapists and researchers misunderstand when they say that the spoken does not ‚match the body language‘, f. i. when somebody says with a sad look on the face; „I am so happy“. I see it such that the words „I am so happy“ is the social offer to the bond with the other, as the sad look on the face belongs to an inner and most probably sad talk which the person most probably is not interested to tell the other. Therefore, as long as the other does not wish to tell from his inner talk I see it as ordinary politeness neither to see how the inner talk is presented in the bodily expressions. According to that it should be a running challenge for the therapist and researcher to evaluate which of a person’s expressions are offers to his participating in the social bonds and which are not. Laurence Singh, a psychotherapist and participant at a workshop I held in Johannesburg, march 2001, offered me a phrase, „a social offering,“ to describe those expressions that contributes to a social bond, different from the expressions that are personal and not meant for a social bond.

- The movements of the expressions, not at least the breathing movements, which form and bring forth the inner and outer voices are personal. The breathing movements ar as personal as finger prints. Lev Vygotsky said: „We are the voices that have inhabitated us“ (Morson, 1986, p 8). Mybe one could nuance that to: „We are the movements that form and bring forth the voices that have inhabitated us“.

- In his time Heraclit said; „Everything is in change, but the change happens according to an unchangeable law(logos), and this law comprises a mutual interplay between opposites, but however such that the interply between the different forces makes a harmony, in total.“ (Skirbekk, 1980, p 29). Maybe one could dare to make some small changes to: „A person is in movements, but the movements happen….“ Or even to: „A person is movements, but ……..“. When we stand, and stand in balance, those muscles that bend in the knees and the hips are active at the same time as those muscles that strectch the knees and the hips are active.

- When one speaks out loud one tells something to both others and oneself. At the moment I think that the most important person I speak to is myself. As mentioned in v) the expressions are formative and also forming our understanding. Ludwig Wittgenstein and Georg Henrik von Wright wrote that our own speaking bewitches our understanding. We can not not be bewitched by our own speaking. When we belong to a community, f.i. a professional community, we certainly have to talk the language of that community. One has to be willing to let oneself be occupied by that language if one wants to stay there. If this language uses the verbes to be and to have without simultaneously indicate context and time, one may, as said before, easily come to understand that human beings are static. Different kinds of language; the language of competition, the language of strategic management, the language of pathology etc. have all their consequences, both for those who are described and for those who describe.

- In 1985 Harry (Harold) Goolishian launched the concept ‚the problem-created system‘. He said that a problematic situation quickly attracts many persons attention. The attracted persons usually make up meaning of ; „how can I understand this?“ and; „what shall I do?“ Two pages ahead in this chapter Maria, who did not want to go to school any more, will be mentioned. That is an example of a problem that creates meanings by others; a system of meanings is created. If two or more persons have the same meaning a talk between them will easily make them repeat and confirm their meanings, and very little new is developed. If two or more people have somewhat different meanings and are able to listen to each other, a talk amongst them will easily create new and useful meanings. If two or more persons have very different meanings, they might find it difficult to listen to each other and may even interrupt and correct each other. When that happens not seldomly the talks break down, and if that happens the really big problem is created.

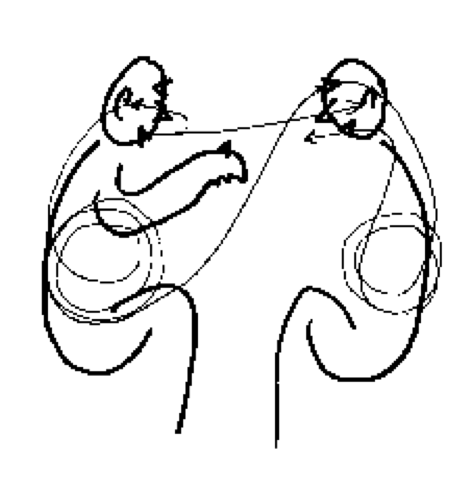

A sketch of a conversation

Tom Andersen

The person to the left is talking and the person to the right is listening. The listener does not only listen to every word, but does also see how the talker receives her own words. The listening will notice that some of the talker’s spoken words are not only received and heard but they do also move the talker. These movements of the talker can be seen or/either heard. Some times a shade crosses the talker’s face, the hands can be closed or opened, there comes a cough, a tear can appear, the person pauses, etc. The listener understands that the spoken words carry a meaning that makes the talker re-experience something she has experienced before without understanding what that is. Not seldomly the listener is carried away and moved by noticing the talker be moved. Those moments when both are moved are good for launching a question or a comment, which in their turn keep the speaker’s movement and the common movement going. A change or an expansion of expressions that move can make a new understanding of a difficult situastion, or a new idea of how one shall take the next step, from this, maybe problematic moment to the next, hopefully less difficult moment.

It is significant that those who want to talk can talk, but it is much more important that those who do not want to talk are given the possibility of not talking.

It is significant that those who want to talk talk of what they prefer to talk about, but it is much important that they shall not talk of what they do not want to talk about.

Nobody talks with whoever about whatever whenever in whatever way; one selects carefully who one speaks with about which issue in which way at which point in time.

It is significant that those who want to talk select their issue and use their preferred words and expressions, and are given the necessary time to express this. It is important that the talker is not interrupted.

It is significant that the talker can say what he wants to be heard, and not necessary what the therapist or the researcher wants to hear.

A meeting before the meeting, and then the meeting

Some practical guidelines

This happened in Finland, in Jaakko Seikkula’s area. It was part of a local, three years training program. Seikkula has written extensively from their own work (Seikkula, 1995, 2001 a-d).

It was the team of three that wished a family they were working with should come, and they wanted me to be active in the talk that fifty trainees and trainers in the audience should follow. The room was an amfi theater in the beautiful local library. First I asked as I usually do: is there something you want to tell before the family comes, or can we wait until they are here? One in the team said: there were many families we could chose between, but we picked this particular one, and an other continued: because we in the team are occupied with the fact that many in the family have been psychotic. We are uncertain how we shall understand that in relation to this case. Maybe it is hereditary that the daughter does not want to og to school and has dropped training of driving car and will not be with friends and most probably hear voices? My comment was now as so often as a question, and based on the thought that maybe the family already has enough concerns and maybe should be released from having the teams‘ concern in addition thgeir own: if the family had been here, how would it be for them to hear a discussion amongst us about the team’s concerns? The team said we should wait for the family. I hinted that maybe the family’s presence and participation was not necessary for the discussion of the team’s concerns.

Before the family came I asked the translator if she had any preferences for the translation. She had not, and I thought that I have had the same answer all over the world; translators ‚are‘ extremely flexible. Usually families prefer to speak for a while and have that summarized. I told the translator to give the family the time they needed, and you summarize it your way. Do it the way you feel comfortable with. ‚Correct‘ translation is not necessary. It is important that the person in the family that speaks can see that the person who hears the words also receives them. As long as I do not understand the local language, I can not be that person. It is good if the translator as much as possible take the therapist’s position (in this case mine).

A mother and her nineteen year old daughter entered the auditorium, high up in the back, and walked slowly down to the ’stage‘ which was deep down in the front of the room. The mother, Sara, was very concentrated and did almost not notice the attendants. It felt as she was very occupied by something. It was as it was written in her eyes: I have brought an agenda with me, and I need help! The daughter Maria followed the mother carefully and saw and copied what the mother did. They sat down close to each other. The mother sat with her legs side by side and one hand embraced the other hand; the one hand rested in the other hand. They did not squeeze each other. The daughter had her legs crossed. The arms shifted between being crossed and the one hand searching to her mouth.

I excused myself for not being able to speak their language and had to belped by a translator, and asked; how would you like to have the translation? They did not understand, so I said: Do you want the translation word by word or is it better to talk for a while and have it summarized? They wanted sentence by sentence and that was ok with the translator.

Then I said: Would you like to know more about me than what you have been told? The mother said: Why are you here, and where are you coming from? I told that I had had a long collaboration with those who work here, and that they wanted me to come to their training program, that I had been there often before and that they come to Tromsø where I work at the university, and also: We had a short meeting before you came. Would you be interested to know what I was told? They wanted and I said that they were selected as the one family to come amongst many other possible, that I had heard that Maria’s father had been a psychiatric patient and that the team was occupied by that, and that I had said to the team that we maybe could have a meeting about that issue without the family present. I had also been told that Sara was divorced from Maria’s father 10 years ago, and also been told that Maria at the moment neither preferred to og to school nor training for car driving nor be with her friends and that Sara is concerned about that. Sara responded to this orientation by saying: I am so glad to be here, her hands opened carefully and were laying side by side, and she told that many relatives had been to the psychiatric hospital; Maria’s father’s mother and also father’s mother’s father, also Maria’s older sister Marta and their father’s brother had been in similar situations. This uncle committed suicide.

I asked if she had more children, and she told that Johanna was her oldest daughter from a previous marriage. Where is Johanna now? I am not sure, she uses drugs and she is in the streets in a nearby city. When was last time you met her? 3 years ago. Sara became divorced when Johanna was 3 years old, and Johanna was taken care of by her father and father’s mother, and Sara was not allowed to see her daughter. Do you think Johanna has missed you these years? Yes, the hands found each other again, and she looked intensively at the translator and me. Have you missed her? Yes, her eyes filled with tears, and she saw intesively at us, she has written me and asked if she could come to us. To come home. Her father would not see her more. But I am afraid that my two other daughters might start using drugs. To Maria: when was last time you saw your sister? 3 years ago. Do you miss her? A bit. So, both of you miss her? Both nodded and Maria did not know where she should keep her hands, one hand searched first towards her mouth, then came back to the other hand. I said: It sounds like Johanna is lonely? Sara nodded and looked intesively at us and her hands held each other firmly, and I thought (maybe your feel lonely yourself?). Sara broke out spontaneously: I have so much pain! There came a quietness in the room and a pause, and I asked: Where in your body is your pain? In the heart and in the thoughts. Long quiet pause. If your pain found a voice what would it say? It would scream! With words or without words? Without words!! She looked intesively at us as if her eyes said: help me! Who would you like to receive your scream? God. How should God respond to your scream? She now kept her hands tight together and said she hoped God could take care of her three daughters. There came a long pause and it was very quiet in the room. Nobody in the room made the smallest movement. Everybody seemed very moved. Including the translator and myself.

I asked the three in the team what they had been thinking, and the second therapist had been much thinking of the possiblity of Maria hearing voices, and I asked: Would it be more interesting to know more about that in stead of what Sara just told? The therapist became uncertain and could not find an answer. The third therapist said that she was very moved by what she heard of Johanna. She had never heard that before. Sara had at this point crossed her legs and her hands held on the knees as she listened intensively.

I asked if Sara had had a chance to think to the future. As her hands grasped each other again she said she was very worried about the future. Do you have any adult to turn to and talk with? No, she had not. Do you have a mother or a father to talk with? No, her father died when she was 3 years old, and the new man she married shortly after did not want Sara’s mother to be with Sara. So, maybe you also have felt lonely? She said: my daughters are all I have and cried quietly, and there became a big silence in the room. Maria had at this moment lifted one hand to her mouth; did she try to say something? I asked if somebody some time had been close to her. Somebody who was close and understood her? Father’s mother and father’s father had; in their presence she felt understood and protected. They both died when Sara was teenager. If they had been here now they might have helped you? Yes, she cried silently and looked down to her hands.

Now, in these moments I had to consider all the time if it was too difficult for her to talk; if that was the case I had to pick an other issue it was more easy to talk about. According to those impressions I received, I determined to continue; They would maybe have understood your worries and pain and fear for the future? Yes. If they had been here, maybe you did not have to scream to God? No. Her tears were streaming. If your grandmother had been here, what would she have said? Little girl, you have been so good to your daughters! What would you say back! Grandmother I love you so much? And what would she then do? She would put her arms around me, and I could smell her. She smells so good!

Many in the audience wept. Silently. Maybe you could bring them a bit back to your thoughts, maybe that would make it better? It feels less painfull when I speak of them! To Maria: would you like to say what you have been thinking? I have understood that my mom has had pain, but she never said anything. I did not know anything about her grandparents. How would it be for you if your mother took your to their grave and also told a bit about them? That would be good. Was it better for you to hear about your mother’s pain, or would it be better not to hear? It was better to hear. Maybe your mother would protect you and your sister from hearing about her pain and fear for the future? Yes, maybe.

When Sara was asked how it had been to there, she said it was good for her to have a listening audience. Maybe you and Maria would like to hear what they have been thinking? Both would and I turned to the audience and encouraged them to talk to me. That would be better for the team and the family. If the audience talked with me, the team and the family could choose either to listen or let their mind go other places if that felt best. If the audience talked to them or looked at them when they talked the team and the family would be forced to listen to them and could not let their mind travel other places. The first three of them said that they had been very moved by Sara’s considerations for her daughters. I asked if there was a grandfathers voice in the audience, and a man said it had made a big impression on him that Sara despite her own pain had so many thoughts for her daughters. Is there a grandmother’s voice present? A whitehaired woman said: when I listened to this conversation I thought of a visit I made to my daughter and granddaughter yesterday; I thought how important it is for my granddaughter to have a mother, as it is for her mother to have a mother.

It felt that the meeting was close to a natural end; an outsider as me shall not ‚open‘ too much, it was important that the team and the family found their natural way to continue. Both Sara and Maria took farewell with firm handshakes and firm looks, and Sara said: and, it was important to have a commenting audience.

Next week Sara and Maria told that the talk was very useful, but hard because it was painful. Maria had thought in the talk that it might be too much for the mother and she had thought that she might have stopped it. But the mother said it was not too much. They all thought that Maria should start school again.

One in the team wrote 3 months later: „Dear Tom! I have met Maria and Sara last week. They both are well. Maria doesn’t have any psychotic fears or voices anymore. She can meet friends and wants to go to school in August. They send greetings to you. Be well and have a nice summer! B.“

Some after-thoughts

Since the pain had been brought to the open, maybe one could at later occasions hear if Sara’s grandparents could comfort in more ways. In her pioneering work Peggy Penn often encourages those she meet to write a letter (Penn, 1994, 2001). She would maybe have asked Sara to write a letter to her grandparents and told her to bring the letter with her to their next meeting and read it out loud. Peggy Penn would most probably also have asked Sara to write a return-letter; from the grandparents to her self. This might have brought the voices of the grandparents to Sara’s inner talks, and these voices might balance the voice of pain and the voice that feared the future.

Sara’s expressed fear for the future could be a starting point for this: I understand that there is a part of you that fears the fiuture. If that part of you found a voice what would it say During the ‚investigation‘ of that question it is important to go slow and be sure that Sara, when she speaks all the time becomes moved by her own words. If she is not moved of her own words one should not proceed. But if she becomes moved by her own words one could continue: is there an other part of you that has other thoughts or feelings or a hope about the future? If she confirms one could ask: if that part of you found a voice what would it say? When the two voices, which hopefully will balance each other, are heard, one could say: a voice need a home to stay in, if the fearful voice should be put in your baody where should that be? In the same way is the other voice given a home. What seems to be very important is that the therapist does not take side with one of the voices and not with the other, neither encourages the one voice to control the other voice. It is important that they can live side by side as in every peacework.

Some closing comments

The team offered their concern for their participation in the meeting, Sara offered her intensive presence.

What shall one select to start from? Usually, when all are present at the start, it is helpful to ask all how they want to use the meeting. Everybody has a chance to respond, and all answers are remembered as correctly as possible. When all have responded, one at the time, one goes back to the person who responded first and let that person talk of what she or he wants to be heard. Then speak with the person who responded as number two, and so on. In this case the team responded first in the family’s absence, and I asked myself when Sara and Maria entered the room; which expression, the team’s or Sara’s is pressing on the strongest? I chose to answer myself: Sara’s.

In the work mentioned here, it was important first to find out with the the team and the family how we should collaborate before we started the collaboration. The thoughtfullness about the Other must come before the thought of what the other is. This is a bit ‚Levinasian‘ idea. Emmanual Levinas‘ thoughts are in a very fascinating way written about in a norwegian essay (Kolstad, 1995). When Levinas opened a door for the Other he said; „Aprez vous!“ and then he commented that gesture by saing: „this is my philosophy“. He preferred to put the philosophy of ethics before the philosophy of ontology.

When Sara talked, it was very important to listen to every word she said and to see how here own expressions touched and moved her. She searched after and found those expression that helped her to find a meaningful step from the one moment to the next. Harry Goolishian constantly reminded us: „Listen to what they really say, and not to what they really mean!“ In the moment we listen to what they really mean, we interpret what they say in our own perspective, which means that we make up our meaning of what they say. For the listener, being therapist or researcher, it is important to throw out the inner voice that says: „What is he really meaning?“ or; „What is she trying to say?“ There is nothing more then what they say. So, we have to listen carefully to what they say.

My wish is at the moment that we stop talking about therapy and research as human techniques, and rather talk of it as human art; the art to participate in the bonds with others. If we exclusively started to use the word ‚human art‘ how would that bewitch our understanding and our lives?

It has been of outmost significance for me to think the work that is sketched in this chaspter has fully been based on practical experiences (‚empiri‘) where the most important has been to find a way of collaboration where all participants are protected against having their integrity and identity humiliated. When that way of collaborating is found time has come for the ‚theories‘, which I in this chapter have preferred to mention as assumptions.

REFERENCES

Andersen, T (1995): Acts of forming and informing. In: Friedman, S (ed): The Reflecting Team in Action. New York: The Guildford Press.

Anderson, H (red) (1995): Från påverkan till medverkan. Stockholm: Mareld forlag

Bakhtin, M (1993): Toward a Philosophy of the Act. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Gergen, K J (1994) Toward Transformation in Social Knowledge. Second edition. London: Sage publ.

Grayling, A C (1988): Wittgenstein. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ianssen, B (red) (1997): Bevegelse, liv og forandring. Oslo: Cappelen Akademiske forlag.

Kolstad, A (red) (1995): I sporet av det uendelige. En debattbok om Emmanuel Levinas.

Oslo: H.Aschehougs forlag.

Morson, A C (1986): Bakhtin. Essays and Dialogues on His Work. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Penn, P (1994): Creating a participant text: Writing, Multiple Voices, Narrative Multiplicity.

Family Process: 33:3: 217-232

Penn, P (2001): Chronic Illness: Trauma, Language and Writing: Breaking the Silence. Family Process: 40:1: 33-52.

Sampson, E E (1989): The Deconstruction of the Self. In: Shotter J (ed): Texts of Identity London: Sage publ.

Seikkula, J (1995): Treating Psychosis by means of open dialogue. In: Friedman, S (ed): The Reflecting Team in Action. New York: The Guildford Press.

Seikkula, J., Alakare, B & Aaltonen,J. (2001 a) Open Dialogue in psychosis I: An introduction and case illustration. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 14, 247-266.

Seikkula, J., Alakare, B & Aaltonen,J. (2001 b) Open Dialogue in psychosis II: A comparison of good and poor outcome. Journal of Constructivist Psychology 14, 267-284.

Seikkula, J., Alakare, B & Aaltonen,J. (2001 c). El enfoque del Dialogo Abierto. Principios y resultados de investigacion sobre un primer episodio psicotico. [Foundations of open dialogue: Main principles and research results with first episode psychosis]. Sistemas Familiares, 17, 75-87.

Seikkula, J., Alakare, B. & Haarakangas, K. (2001 d). When clients are diagnosed „Schizophrenic“. In B. Duncan & J. Sparks (Eds.) Heroic clients, heroic agencies: Partnership for change. Ft Lauerdale, Nova Southern University Press.

Shotter, J (1993): Conversational Realities. London, New York: Sage publ.

Shotter, J (1996): Some useful quotations from WITTGENSTEIN, VYGOTSKY, BAKHTIN AND VOLOSINOV Presented at the Sulitjelma conference in North Norway, June 13th to 15th 1996.

Skirbekk, G (1980): Filosofihistorie I Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Tranströmer, T (1997): Dikter. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers forlag

von Wright, G H (1990): Wittgenstein and the Twentieth Century. In: Haaparanta, L et al. (eds): Language, Knowledge and Intentionality Helsingfors: Acta Philosophica Fennica 49.

Von Wright, G H (1994): Myten om fremskrittet. Oslo: Cappelen’s forlag.

Vygotsky, L (1988): Thought and Language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wittgenstein, L (1953): Philosophical Investigations. Oxford Blackwell.

Norsk utg (1997): Filosofiske undersøkelser. Oslo: Pax forlag.

Wittgenstein, L (1980): Culture and Value. Oxford: Blackwell.

Øvreberg, G (red) (1986): Aadel Bülow-Hansen’s fysioterapi. Tromsø, Oslo: I kommisjon med Norli forlag.